A Simple Way to Keep Boards Smart and Nimble

Consumer Electronics Association CEO Gary Shapiro doesn't get hung up on process when it comes to finding board leaders and getting them ready to lead.

Not everybody agrees on what’s most important when it comes to managing boards. But Gary Shapiro is pretty sure about one thing: It doesn’t involve arguing over who’s taking care of the drink tab.

Shapiro, president and CEO of the Consumer Electronics Association since 1991, was recently gobstopped by an online discussion about reimbursement for board members’ alcohol consumption. “I thought, ‘If we talked about these sorts of things in my board meeting, I’d shoot myself,’” he says. “[Board members] are giving you something, and you’re worried about whether you’re paying for their Bloody Mary? When I hear something like that I think, no, nothing’s changed.”

Too many boards, Shapiro says, are “working at the five-foot level and not the 30,000-foot level.”

Shapiro has long been tubthumping on behalf of better board stewardship, both in terms of how potential board members are identified and vetted and how they’re managed when they’re in the room. But though CEA has a sizable budget, one of the world’s largest tradeshows (the Consumer Electronics Show), and a high-wattage board, Shapiro doesn’t dwell much on a convoluted nominating process or on lengthy orientation sessions for new volunteer leaders. Indeed, the hallmark of CEA’s process is a simplicity that’s transferable to many associations, regardless of size and budget.

First, the criteria. For years now, CEA has scored potential board members on ten categories, with Shapiro and his nominating committee rating each on a scale of one to ten. The list remains unchanged from when he shared it in an interview with Associations Now in 2012:

- Demographic diversity

- Corporate diversity

- Strategic thinker

- Experience

- Association mindset

- CEA engagement

- CES participation

- Commitment

- Travel flexibility

- Enhances CEA reputation

(The toughest criterion on that list to satisfy? “It’s hard finding highly qualified female CEOs who aren’t already in demand elsewhere,” Shapiro says.)

The nomination process has the useful side benefit of selecting for people who are already attuned to the demands of volunteer service and the particular structure of an association. To that end, Shapiro doesn’t waste much time on formal orientation. “If you want top people, you’re not going to spend a lot of time on training or learning,” he says. But that’s not to say that even the most dynamic board won’t have its drink-reibmursement issues—or, as he puts it, “working at the five-foot level and not the 30,000 foot level.”

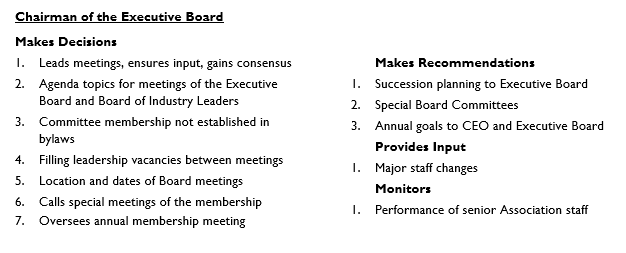

To forestall that, Shapiro does his share of framing strategic discussions during the early portions of meetings. But he also presents board members with a simple matrix that lays out the particular roles of the CEO, the chair, and the board, when it comes to deciding, informing, and recommending. The chart breaks down the purpose of the board meetings—and automatically stifles any effort to move the discussion outside of the assigned boundaries. Below is a sample section of the document, showing the breakdown for the board chair.

Outside the boundaries of a strategic discussion, that is. Shapiro is comfortable with dissent and disagreement about CEA’s direction, so long as it moves on a strategic level. Indeed, part of the point is for the group to become educated on what they’re unsure of, not ratify a leader’s certainties. “At the beginning of meetings I remind them of what we’re trying to seek, what the culture is, and what I need help and input on,” he says. “It’s ok going into a meeting not knowing an answer….I ask them for help on the things they can help with.”

Shapiro finds that kind of flexibility essential, and bemoans the struggles of associations that he says he believed hurt themselves by failing to act except by unanimous consent by its members. Flexibility is critical for effectiveness, and that’s a duty that falls to both the board and the CEO. “I think it’s very important that every CEO has a good understanding with their board about their respective roles, and that they be empowered. If the board is micromanaging the CEO, then everybody loses,” he says. “And If you try to play your board [as a CEO] and not use them as an asset, you’re going to get in trouble as well.”

What vetting process for board members do you use, and how do you get them up to speed quickly? Share your experiences in the comments.

(iStock/Thinkstock)

Comments