Putting Humans Behind the Machines

For years, Amazon has quietly built an army of online users who work on tiny tasks for low pay. For associations, the tool it created, Mechanical Turk, could prove an effective way to do market research and manage important but tedious tasks. But it has its pluses and minuses.

Nine years ago, Amazon took one of its earliest steps away from simply being a retail giant.

To this day, the innovation is proving immensely helpful for testing, getting opinions, and doing research. Oddly enough, it’s powered by people—thousands of them.

Before Amazon became known for the cloud or for tablets, the firm launched Mechanical Turk, a service that allows organizations to pay small amounts for workers to conduct a series of microtasks (often a few cents per task)—work that takes a few minutes at best and can only be conducted by humans, not machines.

It was kind of a crazy idea that nobody knew what to do with at first. It drew massive hype, but after its initial buzz, it became a modest, utilitarian part of the web—it’s never gone away, but it’s never been a limelight-stealer.

But the microtask is having a bit of a moment right now, as organizations and companies alike have found ways to make it work for them. A couple examples:

Last week, The Washington Post noted that the Federal Election Commission had hired a firm, Captricity, that promises to digitize and put online, in a matter of hours, the lengthy, detailed printed documents that the commission receives from political campaigns. How? Short version: The company has figured out a way to use Mechanical Turk to enlist people (“Turkers,” as workers on the platform are often called) to enter certain data from the forms, and then uses machine learning to fill in the gaps. Pretty cool, huh?

In a Priceonomics blog post published earlier this month, author Rosie Cima noted that the platform has been a boon for behavioral science in the academic world because it exposes significant numbers of people to potential research studies. “But even if Turkers in total ‘are not representative’ of ‘any population,’ researchers can slice them down into cleaner demographic samples,” she explains. “Just like they have the option of only allowing Turkers with a certain quality score to complete their tasks, they can also do things like only allow U.S. residents.” The pool of potential research subjects, she notes, is particularly strong in India and the United States.

Is it Ethical?

Admittedly, services like Mechanical Turk raise some ethical questions. The complaints started back in 2005, and they’ve never really gone away.

A 2012 piece by East Bay Express writer Ellen Kushing highlights the main arguments:

Numbers are hard to track and vary from worker to worker, but [New York University professor Panos Ipeirotis] has estimated the average hourly wage [for Turkers] to be roughly $2, while Joel Ross of UC Irvine’s Department of Informatics places it closer to $1.25—and whatever it is, it’s certainly lower than the federal minimum wage of $7.25.

But that’s not all: Embedded in Amazon’s 5,200-plus-word Terms of Use agreement is a clause that essentially allows employers to reject an employee’s work whenever they want, no questions asked. Talk to enough Turkers and most of them will relay some version of the same story: They completed a task, all or part of which was rejected, and never found out why.

While active Turkers have struggled to deal with these issues, they’ve worked to find common ground: Earlier this year, an online community for active Turkers, Dynamo, created a set of worker guidelines specifically for the academic community, which include standards for ethical pay. So far, 28 researchers from schools such as Harvard, Carnegie Mellon, and Stanford University have agreed to follow the standards.

Interestingly, though, Priceonomics offers these two points: Research shows that most people who work on these tasks in the U.S. aren’t in it as a full-time gig but as a way to kill time and earn some extra money on the side. And dedicated users in India can make amounts approaching an average wage for that country.

Nonetheless, it’s worth considering these issues when deciding if using Mechanical Turk is a good idea for you.

A Few Turking Ideas

So what could you use an army of modestly paid workers for, anyway? Here are a few of the more common ideas out there:

Instant focus groups: Testing a new website with a certain audience? You can hop on a service like Mechanical Turk and get quick feedback from a small audience for pennies on the dollar. (Google recently did this when testing out a new interface for its mobile search.) Likewise, if you want to test messaging with a large number of people over a short period of time, it’s a great way to do so.

Conduct a study: For social science-related research, Mechanical Turk and similar services are well suited for posing quick questions. Want to research how people feel about a certain topic related to your industry? It could be a great way to test the waters.

Growth hacking: Occasionally, Mechanical Turk publishers hit on truly brilliant uses of the platform. A good example comes from the firm ThingsWeStart, which used a combination of the Google News API and Mechanical Turk to collect contact information for reporters covering a relevant beat. It only cost $10.50 to collect the info over a couple of days and earned the firm 13 separate press write-ups.

Offload annoying tasks: Auditing old content on a website to make sure information is current, or if links still work, is a pain. But having a Turker do something like audio transcription could allow you to refocus your staff members on less tedious tasks. That taxonomy you’re building could become a little less taxing.

Does This Make Sense for Associations?

You might be wondering: What the heck does this have to do with the association space? As it turns out, it has a lot in common with a concept that’s been often touted among association pros.

The idea of micro-volunteering—asking members to assist in very small ways, such as having them greet attendees at an event, set up or tear down a meeting room, or comment regularly on a community forum—is effectively the same kind of territory. As my colleague Joe Rominiecki pointed out last year, they help build a sense of ownership in a community.

But sometimes a task is too small or tedious to ask a member to do. Or maybe it requires fresh eyes that members don’t have because they know you too well. Maybe research important to your field requires people who know little about the space in which you work. You lose the ownership and engagement elements, but you could gain some useful benefits in the process—such as a little less pressure on an overworked small staff that needs the extra bandwidth.

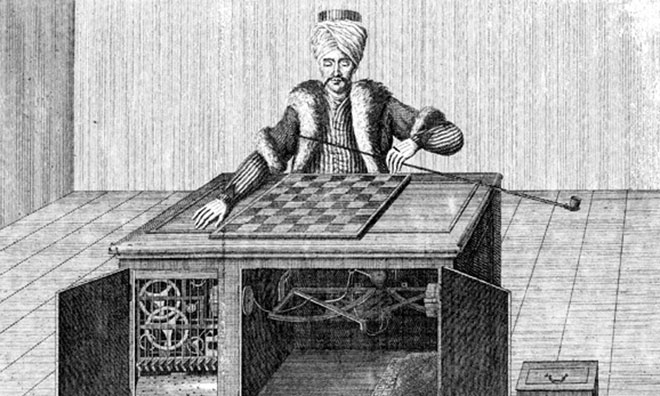

Mechanical Turk—the name, by the way, has a great backstory—isn’t for everyone. But given the appropriate task and business need, it could prove a fascinating boon for the right organization.

Now if you’ll excuse me, I have a few sheep to draw.

(Wikimedia Commons)

Comments