Starting Line: Association Startups Take Their Marks

The association startup space is budding just as much as the for-profit space is in Silicon Valley. Check out three examples of new groups that are starting to make an impact on fresh industries.

Association executives who were around in an organization’s early days might look back on those times fondly—long hours and late nights, learning by trial and error, and panicking when growth exceeded expectations. For associations still in their formative years, however, making it through each week, still standing, is cause for celebration.

There are more than 90,000 trade and professional associations in the United States, and new ones start up more frequently than you’d think. Here are the stories of three relative newcomers to the sector—each in a different stage of development—and the obstacles they’ve overcome, the lessons they’ve learned, and where they’ve found success along the way.

National Cannabis Industry Association CEO Aaron Smith. (Willie Petersen)We don’t want to be Big Tobacco or Big Alcohol.

The Move to mainstream

National Cannabis Industry Association; Founded 2010

At the ASAE Annual Meeting & Exposition in Nashville last August, National Cannabis Industry Association cofounder and Executive Director Aaron Smith deflected a few smirks when he mentioned his organization. But with time, he says, most people understood that NCIA represented an industry just like any other.

“People were surprised to hear about this association when we started,” Smith says. “But now it’s becoming less taboo and more mainstream. They realize the challenges and issues we face—like managing growth—aren’t that different from those of other associations.”

NCIA was founded in 2010 by Smith, a public advocate for marijuana policy reform, and Steve Fox, an attorney who has written state marijuana laws, to promote the growth of a responsible and legitimate cannabis industry.

The industry has experienced phenomenal growth since 2012, when Colorado and Washington state legalized recreational marijuana use. In 2013, NCIA had 118 member businesses, ranging from marijuana dispensaries to packaging companies; that’s grown to more than 800 members today. Smith would like to see that double.

It took effort to educate some cannabis business owners, many of whom had been working underground, about the purpose of a trade association. This being a very face-to-face industry, that education involved one-on-one meetings with business owners, events about the work the association does, and demonstration of the value of the association’s work. But now, NCIA has joined the ranks of successful startups, having hosted its first national conference in June, with program offerings such as CannaBusiness 101 and Cannabis Policy and Reform.

“We don’t want to be Big Tobacco or Big Alcohol,” Smith says. “But the opportunity the cannabis industry has now, having come out of prohibition, is exciting. It can be a different type of industry—politically active, transparent, and responsible.”

NCIA has a three-tier membership structure, weighted for voting, with top-tier members (dues are $500 per year) eligible to run for a seat on the board of directors. Smith, who works out of a Denver office with eight staffers, sits on the board, which has quarterly meetings to establish strategic direction and budget.

He says he’s learned how important it is to listen to what the members want. For example, he thought NCIA’s lobbying work would be a huge draw—after all, they have two full-time staffers and a contract government relations advisor in Washington and will open a brick-and-mortar office this spring. But he’s finding that members really want to network, and so far, they have considered the DC connection more of a fringe benefit.

Smith is also realizing how much NCIA can learn from other associations around common issues, rather than reinventing the wheel. One thing he learned at the ASAE conference last year is that NCIA needed to boost its content through online newsletters. “We realized we needed to be a better information resource and learn how to highlight our members and do more than just promote them within the association,” Smith says. “We need to do things like go to Capitol Hill with short videos about what businesses are doing in the industry.”

“It’s been a wild ride,” says Smith, who worked “insane hours” for no salary at the beginning. At least the salary part has changed. “I will be involved at least until prohibition has ended. Then I can hand over the reins,” he says.

The FAA appears to have considered the voices of the drone community.

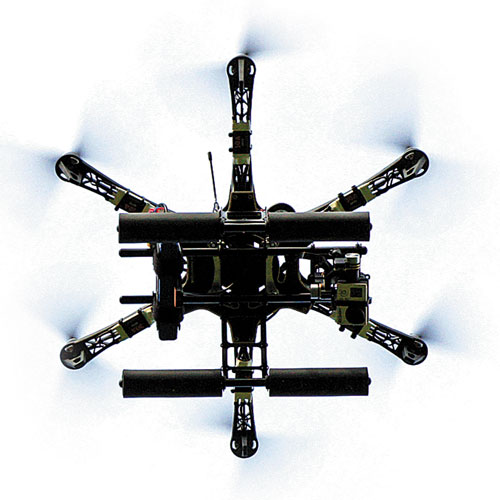

From Quiet Hum to Loud Buzz

Drone Pilots Association; Founded 2014

Last year, Peter Sachs was well known in certain circles as the “drone guy,” a vocal commercial-drone advocate and publisher of Drone Law Journal. He didn’t expect to also become the “association guy.”

He’d planned on launching the Drone Pilots Association (DPA) in 2015 to represent the interests of all commercial and non-hobbyist drone pilots—those who operate the devices as part of a business (from aerial photography to farming) or for search-and-rescue, fire service, or law enforcement efforts. His goal was to provide benefits similar to those offered by the Aircraft Owners and Pilots Association: legal services, insurance, and education.

But last June, the Federal Aviation Administration published an interpretation of its Special Rule for Model Aircraft established by Congress in 2012, in which the agency affirmed its authority to regulate the use of unmanned aircraft operated for commercial purposes. The interpretation required drone operators to obtain prior permission to fly within five miles of any airport and, Sachs says, suggested that commercial drone use was illegal.

“The only law about commercial use being illegal is this interpretation,” says Sachs, a non-practicing public interest attorney who works as a private detective. He is also a licensed commercial helicopter pilot who flies for the fire department. Sachs felt it was his job to challenge any efforts to regulate drones, and he knew a lawsuit was in order. But he also realized it would have more bite if it came not just from him, but from a large group affected by what he calls “the FAA’s overreach and intimidation tactics.”

So six months before he intended, Sachs created DPA on July 18. He rushed to build a rudimentary website using WordPress and announced the no-fee association through Twitter. Within the first 24 hours, he had 600 members; within three days, membership was 1,000. Sachs began raising money to fund a legal challenge and hired a drone lawyer, who filed the lawsuit on August 22.

In February, the FAA released a new version of its proposed rules. But Sachs says his lawsuit against the FAA is proceeding because “the proposed new small drone law is just that—proposed. That said, I am pleased and encouraged that the FAA has decided to propose a sensible, safety-oriented approach to small drone rulemaking. The FAA appears to have considered the voices of the drone community.

“[The association] is still in a holding pattern because of the lawsuit,” he says. Even offering training for a fee is illegal, according to the FAA interpretation. After the regulatory standoff, DPA plans a fee-based model, offering education, training, an insurance program, and legal services.

In the meantime, Sachs, a one-man show, admits DPA is “a pretty weird entity.” But he has faith that the association has a strong future ahead. “The proposed rule shows it is possible to keep our skies safe while also ensuring U.S. aviation leadership and innovation.”

A Quest for Workplace Equality

Association of Transgender Professionals; Founded 2013

When Denise Norris created the Association of Transgender Professionals (ATP), she envisioned it as a LinkedIn-type of network for gender diversity—a place where transgender individuals could talk about workplace issues and facilitate mentoring and networking. Yet she faced countless unknowns.

After all, part of Norris’ goal was to test the waters and find out what strategy to pursue in the quest for workplace equality. But she knew a couple things for certain: Membership associations have completely changed in the era of social media, and this was an empty niche—the members of existing transgender groups seemed to be more focused on issues other than their jobs.

Norris started ATP as a Facebook page in 2012, and the initial response was robust, with more than 100 membership requests a day. She then formed an unincorporated association in January 2013, with a focus on economic advancement for members of the transgender community.

“We knew what we wanted to accomplish; we just weren’t sure the best vehicle for doing that,” says Norris, who has been working for equality for the transgender community for decades. She found that most members in the Facebook group couldn’t concentrate on workplace issues because they were simply trying to survive. But she had a larger purpose for those who had begun to thrive: reinvesting their time, money, and education to make a difference.

In 2014, the association evolved into the nonprofit Institute for Transgender Economic Advancement. Through sponsorships, the group is spearheading initiatives that focus on economic equality and justice, such as corporate diversity training around gender authenticity and an incubator program for projects related to the economic advancement of ATP’s members.

ATP still exists as a professional networking group, now with 14,000 non-dues-paying members. Facebook posts range from listings for trans-friendly jobs to queries about work situations or discrimination lawyers. Norris runs the two organizations (while still working full time for a global consulting firm), along with seven volunteer moderators around the world who monitor Facebook. This year, Norris would like to see ATP membership raise money, create bylaws, and form a leadership council.

“When you’re forming a large membership association around a common topic, don’t lock yourself into a path,” she advises others with startup ambitions. “Don’t assume you know what services people want. I didn’t know until we were up and running exactly how the membership itself was going to express itself.”

(iStock/Thinkstock)

Comments