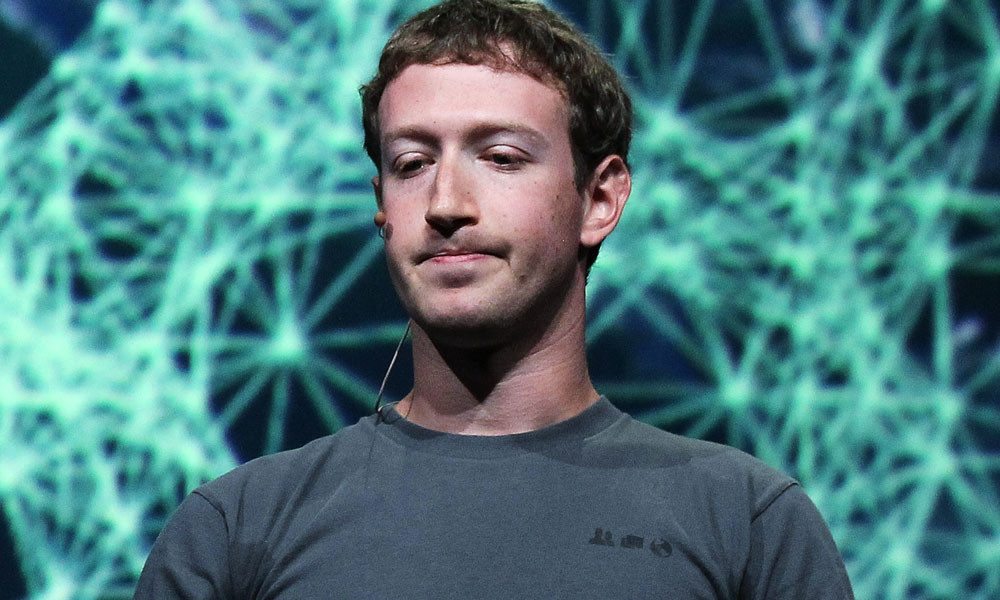

A Leadership Message That’s Hard to Like

Mark Zuckerberg will be forgiven for whiffing his explanation of a “dislike” button. Association execs can't expect the same treatment.

It’s not a dislike button, OK?

Last week Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg hosted a town-hall meeting where he addressed users’ longtime wish for a button that would express a feeling about friends’ posts that was more than just a “like.” This has commonly been called a “dislike button,” and Zuckerberg described it as such at the event: “People have asked about the dislike button for many years… Today is the day where I actually get to say that we’re working on it, and are very close to shipping a test of it.”

Whoops.

Zuckerberg didn’t explain the essence of what the company was up to until about 200 words into his comments—an eternity in leadership terms.

The headline in the New York Times became “Coming Soon to Facebook: A ‘Dislike’ Button,” which missed the point. Zuckerberg made the company’s intentions clear after announcing that Facebook was “working on it”—the goal of a new button would be to allow people to express empathy in contexts where saying “I like this” aren’t appropriate, such as the death of a loved one. “We don’t want to turn Facebook into a forum where people are voting up or down on people’s posts,” he said.

Reporters, though, ran with the first thing they heard, much to the chagrin of some observers. “Damned near all of media have screwed up the story of Facebook’s new button,” media critic Jeff Jarvis wrote on his Facebook page. “This was not a hard story to report correctly. And damn the obvious but wrong headlines.”

We can argue over what appropriate headline would be for Facebook’s move (“Facebook testing ways for users to go beyond the ‘like,’” perhaps). We can discuss the absurdity of this being a news story at all, or debate what an appropriate button should be called (I’m partial to “oof,” myself). But what’s really at issue here, from a leadership perspective, is that what you say first often becomes the story, and that how you frame the story matters.

I wouldn’t presume to second-guess Zuckerberg’s leadership style—I’ve taken a look at both my bank balance and his and acknowledge that he’s a touch more successful. But the dislike button story seems an obvious case where acknowledging the fact that it’s, er, complicated merited emphasis. Zuckerberg did what journalists call burying the lead; the essence of what the company was up to didn’t come until about 200 words into his comments—an eternity in leadership terms.

What Zuckerberg ought to have emphasized was what he said deeper into his comments: “Not every moment is a good moment, right? And if you are sharing something that is sad, whether it’s something in current events like the refugee crisis that touches you or if a family member passed away, then it might not feel comfortable to like that post. But your friends and people want to be able to express that they understand and that they relate to you.”

Facebook will survive this: Enormous and well-financed as it is, it’ll likely deploy some kind of sensibly named clickable empathy-expressing thingamabob, and we’ll likely become collectively inured to clicking on it as appropriate. The stakes may be a bit higher, though, for an association with fewer resources and fewer opportunities to sell its virtues to members.

I thought about this while speaking with Doug Pinkham, president of the Public Affairs Council, for a story about Americans’ attitudes about lobbying. Though lobbying can resonate positively with people if it’s framed as a way for the organization to make a difference in terms of jobs or new markets, many associations undercut their message by being defensive about advocacy. Pinkham described seeing association executives pitch PAC contributions by saying that nobody likes getting involved in the muck of politics, but that’s how the game is played, so we all have to do our bit. “What an uninspiring way to get people to contribute,” Pinkham says.

New ideas, by definition, are unfamiliar to people. It can be helpful to present them in a shorthand manner that can make them memorable. But if that shorthand (“dislike button”) mischaracterizes what you’re trying to accomplish, it’s better to toss it, or at least give it some context.

How do you frame new initiatives to your members, and how do make sure they’re not misinterpreted? Share your experiences in the comments.

(iStock/Thinkstock)

Comments