Executives & Board Nominations: A Delicate Dance

What role should an association CEO play in board nominations and selection? Real-life practices vary, according to new ASAE Research Foundation data, but the best outcomes emerge when executives step gracefully through the process, providing input and guidance in just the right measure.

When Chris Busky, CAE, became CEO of the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) three years ago, one of the first things he did was go on a six-month listening tour of members. Much of the input he received had to do with the makeup of the association’s leadership.

“One of the most common themes I picked up was, ‘The society doesn’t look like me. The leadership of the organization doesn’t look like me,’” he says. “And they were right. It didn’t.” Busky took the matter to IDSA’s board, which has worked since then on diversifying the organization’s leaders and improving its nominating procedures.

It was, Busky acknowledges, a balancing act. CEOs work for the board, and they don’t want to be perceived as putting their thumb on the scale when it comes to the nominating process, installing favorites. However, the CEO typically has closer relationships with a broader group of members than most volunteer leaders do—and, frankly, often knows details about board candidates that make them subpar choices or should disqualify them outright.

How to handle that position? Carefully, association executives say. With some attention and tact, CEOs can play a meaningful role in the board nominating process while avoiding the perception that they’re remaking the board in their own image.

How Far Is Too Far?

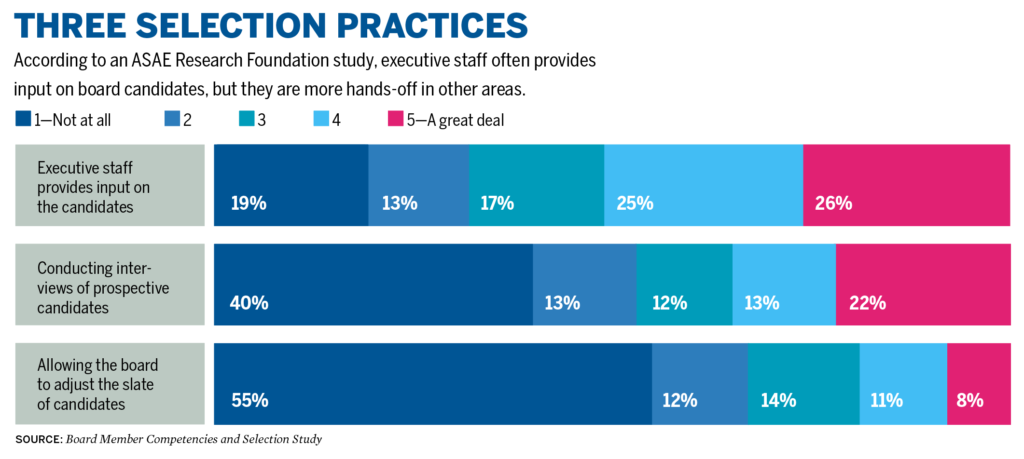

In their 2018 book, Recruit the Right Board, Texas A&M professor William A. Brown and Association Management Center partner Mark Engle, FASAE, CAE, lay out some best practices for board nominations. The CEO often plays a role in that: According to an ASAE Research Foundation survey, slightly more than half of associations said their executive staff provides a substantial amount of input on board candidates. Only 19 percent provide no input at all. (See “Three Selection Practices” below.)

“Leading practices for the CEO during the nominating process are to provide information that aids in the decision-making process without unduly influencing the committee,” Brown and Engle write. But what qualifies as “unduly influencing the committee?”

“People can be extreme about this,” says Engle. “There was somebody who said, ‘I don’t touch that with a 10-foot pole, because I don’t want to be viewed as influencing.’ Frankly, that’s a bit naive. What associations do in governance, and particularly strategy-setting, should be informed by the CEO. What’s important is making sure the process is sound, transparent, and well-communicated.”

Vicki Loise, CAE, CEO of the Society for Laboratory Automation and Screening, plays a formal role in this process as staff liaison to the association’s nominating committee. In a strict sense, her job is to communicate directives from the current board about what it’s looking for. But less formally, she sees her job as championing the characteristics that make for effective board leadership.

“I’m making sure the committee is thinking of people who can perform at the right level,” she says. “In many organizations, the people who end up on your board have probably served in some volunteer capacity, which is great. But you also want those folks who can make the transition from tactical committee work to strategic board work.”

You would be overstepping your bounds if you were telling the committee to nominate or to not nominate an individual for your own personal reasons.

Loise is well-positioned to know who qualifies in that regard, and she says she’ll share that information if it seems relevant.

“You would be overstepping your bounds if you were telling the committee to nominate or to not nominate an individual for your own personal reasons,” she says. “But a CEO does have to do a very delicate dance. The CEO very often knows all the skeletons and secrets that a nominating committee won’t necessarily know about.”

Busky recalls a case from the latest nominating process at IDSA. “An applicant came in that looks great on paper, had a fantastic CV, and has been very involved in the society for many, many years,” he says. “However, that person has had a number of issues with meeting deadlines.” That problem, combined with some “abrasive” behaviors Busky had heard about, prompted him to alert the committee chair. But he left it to the committee to act on that input.

“The chair took it and managed it with the rest of the committee, but I think that’s where the CEO’s insight and knowledge are critical,” he says.

A New Path for Nominations

Greg Wilson, CAE, executive director of the Child Support Directors Association of California, says he’s comfortable with actively recruiting potential board members. But he does so in open communication with his board, urging them to think more strategically about the nominating process.

“I’m pushing the board to think more long-term,” he says. “I presented it with an environmental scan—here’s what I see going on the next three years in the state, and here’s where I see the association in three years. And I asked, ‘If this all plays out, what skills do we need in board members over the next three years?’”

Those conversations can extend beyond board members. One prescription that Brown and Engle make in Recruit a Better Board is for associations to shift from traditional nominating committees charged with developing a slate of potential board members to a “leadership development committee.” The latter looks more broadly for future leaders who can serve in different roles at an association, not just on the board.

“The nomination function is to say, ‘We have three open seats, and we’ve got to fill them,’” Engle says. “The leadership development function is to identify paths of leadership for potential leaders of the future and to develop them.”

That’s something Busky has started to implement at IDSA as an outcome of his listening tour. A leadership development committee is studying how to make the volunteer application process more inclusive. That’s involved looking at how unconscious bias affects the process—white men, for instance, are conditioned to be more confident about nominating themselves than other groups.

“It’s our responsibility as the leadership development committee to be as inclusive as possible and use the right language and not put up barriers for our members to apply for different roles within the society,” Busky says.

Breaking the Bad News

There’s one step in the board selection process where the CEO is unequivocally welcome to participate: when it comes time to talk to the candidates who ran but weren’t elected.

“It’s not easy to call somebody and let them know they didn’t win—that’s a terrible thing to do,” Engle says. But he recalls one case he encountered during research for the book about a CEO and nominating committee chair calling one such candidate. The call “went a long way in keeping her loyalty to the organization.”

“I think it’s as big a responsibility as the nominating process,” Loise says. She remembers a conversation with a candidate who lost in the most recent cycle. “From his point of view, he was thinking, ‘I’m putting in a lot of time and a lot of effort and a lot of my reputation and cachet into this organization. How long does it take before I can reach that point of being on the board?’”

To such candidates, Loise counsels patience but also shares how they can become a better candidate for the next election.

“I’ve had conversations with folks and said, ‘There are a lot of great things here in your CV, but there’s a gap that the committee identified,’” she says. “Usually it has to do with their volunteer work—either they haven’t done enough of it or they haven’t done it at a high enough level for a leadership role. I communicate that to them. And then we find places for them to fill those gaps.”

(filo/Getty Images)

Comments