Behind Closed Doors

An association board may sometimes feel the need to dismiss staff—and even the CEO—for an executive session, but doing so may sow seeds of distrust. A common understanding between board and staff about how executive sessions fit into the organization’s governance practices can ensure they are a useful tool and not a sore subject.

An association board may sometimes feel the need to dismiss staff—and even the CEO—for an executive session, but doing so may sow seeds of distrust. A common understanding between board and staff about how executive sessions fit into the organization’s governance practices can ensure they are a useful tool and not a sore subject.

If you want to ruffle a few feathers at your association’s next board meeting, mention the words “executive session.”

For boards of directors, an executive session—a portion of the meeting during which some or all staff, including the chief executive, are asked to leave—can be attractive when board members want to speak more frankly; indeed, meeting without staff may help to build cohesion as a leadership body. For the staff, however, such sessions can be interpreted as evidence of a lack of trust or confidence, particularly when they come as a surprise and the discussion of what transpired is not shared afterward.

Executive sessions have their purpose, but as they are used in associations today, it’s hard to decide if they’re a best practice, a bad habit, or something in between. Boards and staff tend to view them quite differently. This disconnect seems rooted in a lack of clarity about the role executive sessions should fill. What is their purpose? Who should and should not be included? And should they be held regularly or only as needed?

To answer these questions, we interviewed association executives and attorneys, accountants, and consultants who work closely with association boards. We engaged in spirited exchanges on several discussion forums and conducted a thorough literature review. We learned that there is little agreement about when and for what purposes an executive session should be convened, but we believe that any association can make executive sessions an effective tool if its leaders—both board and staff—build a common understanding of how they fit into its chosen governance model.

“I have an agreement with the board that, as an ex-officio member, I am present at executive sessions except when the board is discussing my performance.” —Christine McEntee, MHA, FASAE, Executive Director, American Geophysical Union

What Is the Purpose?

BoardSource (formerly the National Center for Nonprofit Boards) uses the term executive session for meetings that may or may not include the chief executive. Issues commonly discussed during an executive session with the chief executive present include

- Alleged or improper activities (unless these activities have been perpetrated by the chief executive)

- Litigation

- Major business transactions

- Crisis management

- Roles, responsibilities, and expectations of the board and chief executive.

“We have found that meeting in executive session with our president (chief staff executive) supports a trusting relationship between the board and the president and also allows us to speak more openly and frankly about sensitive issues, like contracts, than we would in the presence of the staff who otherwise participate in board meetings,” says Rick Hess, chairman of the National Frame Building Association.

The reasons to meet in executive session with only board members include

- Discussions of chief executive performance and compensation

- Succession planning

- Legal issues involving the chief executive

- Board practices, behavior, and performance

- A financial audit, often with an independent auditor present.

These lists may even be too long for some.

“I can think of only two reasons to hold executive sessions,” says Jerry Jacobs, JD, a partner at Pillsbury Winthrop Shaw Pittman, LLP, where he leads the nonprofit organizations practice, “because ‘closed’ meetings of competing professionals or business people automatically raise questions about the legitimacy of what is going on. First, if legal matters are to be discussed, all but the most senior staff—those with a ‘need to know’—and counsel should be excluded in order to maintain the attorney-client privilege. Second, if the board is discussing those who would ordinarily attend—staff or consultants—it makes sense to exclude the subjects of the discussion in order to permit a candid discussion by the elected/appointed members of the body.”

Who Attends?

The question of who is included in or excluded from an executive session starts, of course, with who is present at the regular board meeting.

C. Michael Deese, JD, a partner in the Washington, DC, office of Howe & Hutton, Ltd., recommends that meeting attendees other than directors, senior staff, and legal counsel should be invited only for portions of the meeting for which they possess relevant information. “If others are permitted to attend and the agenda includes items of a confidential nature that should be discussed only in the presence of the directors, senior staff, and legal counsel, I would not call this an executive session, but it is ‘executive’ in the sense that it is closed to persons who otherwise attend the meeting,” Deese says.

Excluding the CEO and staff can undermine trust, which is why consultant and author William Mott is opposed to it. “It demonstrates a lack of understanding that the CEO and board chair have different responsibilities and must work together to achieve the mission and vision of the organization,” he says. “Too often this type of executive session includes discussions about issues with which the board has limited or no information, and thus they can devolve into unproductive and inappropriate discussions or even forums to spread gossip.”

Cynthia Mills, CMC, CPC, CCRC, FASAE, CAE, president and CEO of Carolinas AGC, Inc., has established an agreement with her board that aims to avoid such discussions. “I write into my employment contract the conditions under which an executive session can happen and limit that to the discussion of my performance review and compensation,” she says. “This sets a standard that we are partnering together for success.”

Richard Grimes, M.Ed., president and CEO of the Assisted Living Federation of America, takes a different approach, one that makes room for board-only executive sessions while supporting a climate of trust between board and staff. “I have two-part executive sessions at each of my board meetings,” he says. “In the first part, I dismiss the staff and remind the directors that this is the part of the executive session where they can tell me anything they would be uncomfortable saying in front of the staff. In the second part, I leave the room and remind them that this is the part of the meeting in which they can talk about me.”

How Often?

Frequency of executive sessions will follow from their purpose, but it boils down to a simple choice: regularly or rarely?

Deese observes that “if associations limit attendance at board meetings to directors, senior staff, and legal counsel, I do not believe it is a best practice, or even prudent, to provide for a true executive session at every board meeting.”

Stephen C. Carey, Ph.D., CAE, lead strategist at Association Management + Marketing Resources, agrees and notes, “It is certainly not a best practice to have one at every meeting.”

Among proponents of scheduling an executive session in conjunction with every board meeting, the primary reason is to allay concerns that executive sessions are convened only in times of trouble with the CEO or staff. “I have an agreement with the board that, as an ex-officio member, I am present at executive sessions except when the board is discussing my performance,” says Christine McEntee, MHA, FASAE, executive director of the American Geophysical Union. “We schedule an executive session on every agenda—sometimes they are held, sometimes not—to keep suspicions at bay.”

Board-Staff Partnership

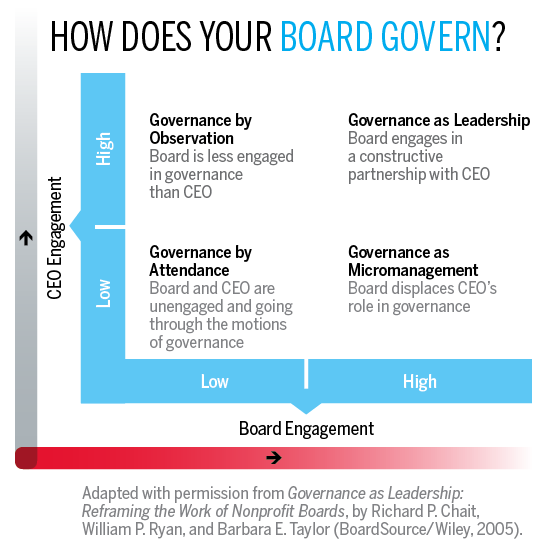

How do we make sense of these conflicting opinions about executive sessions? Governance theory can bring the issue into better focus. In organizations that operate with a shared governance model (see chart on page 64), boards and staff can use the subject of executive sessions to explore their approach to governance and, on this foundation, develop a policy about who should participate in conversations about sensitive matters.

BoardSource recommends that such a policy should cover how to call and conduct an executive session, how to identify the items that are addressed—including the issues from which it is appropriate to exclude staff—and how to properly document and communicate the discussions held in the session.

In an organization in which the board engages in a constructive partnership with the staff, the board chair and the chief executive can work together to plan executive sessions. Inviting the chief executive to participate in most executive sessions sends an important signal that the relationship between the board and the chief executive is paramount and that the board appreciates the executive’s contributions. Establishing a specific time, purpose, and attendee list in advance also helps the chair and the chief executive keep the conversation on topic.

Documentation and reporting are critical, as well. If no staff or legal counsel is present, the secretary should prepare and maintain the minutes of the session, which can be approved by email or at the next meeting. They should be marked and kept confidential. When the chief executive is excluded, the board chair should provide a timely summary of the board’s discussion. Similarly, the chief executive should summarize the session and communicate as soon as possible to the staff who would otherwise be included in the board meeting. If everyone can leave the room confident that the substance of the meeting will be communicated as appropriate, executive sessions can be less of a source of anxiety for those excluded.

The next time the topic of executive sessions comes up, take note of the reactions around the room. If there’s discomfort or disagreement, it may provide an important opportunity to explore the roles of your board and chief executive in governance, determine who should participate in conversations about sensitive matters, and be more intentional about fostering a constructive partnership.

(iStock/Thinkstock)

Comments