Game On: Leadership Lessons From Athlete-Executives

As the world turns its attention to the Olympics, four athlete-executives, two of them former Olympians, tell how pursuing excellence in sports made them better leaders.

Elite athletes are finely tuned, but not just for athletic competition. They apply discipline, focus, and persistence. They master team dynamics. They repeatedly test their physical and mental limits, face failure, and keep going.

It’s no coincidence, then, that competitors who excel in sports may also be poised to excel in other arenas, including association leadership. Allow us to introduce you to four cases in point. In the process of achieving excellence in their sports, these four executives developed skills and learned lessons that they continue to draw on in their nonprofit careers.

In the spirit of the Olympic Games, Associations Now talked with them about victory, defeat, and what they’ve learned along the way.

Embed from Getty ImagesNancy Hogshead-Makar won three gold medals and one silver at the 1984 Summer Olympics. Her coaches taught her how to be a coach today, as CEO of Champion Women.

Finger-pointing isn’t helpful: I had to own my own experience, and what happened would be on me.

The Olympic Swimmer

As a competitive swimmer, Nancy Hogshead-Makar developed a strong work ethic at a young age. She won four medals at the 1984 Olympics: three gold and one silver. But it isn’t the medals she’s most thankful for—it’s everything she learned while training to compete for them.

One of those lessons was that every day mattered, and she had to push herself to get a little bit better every day. “If you have big goals, the time you have to work toward them is precious,” she says. Now the CEO of Champion Women, a nonprofit that advocates for women and girls in sports, Hogshead-Makar has drawn on that work ethic throughout her career as a civil rights lawyer fighting for women in gender equity, sexual harassment, sexual abuse, employment discrimination, and Title IX cases.

During her Olympic training in Florida, while nature lovers floated down the Ichetucknee River, Hogshead-Makar’s team swam upstream— a grueling five-hour workout that entailed trudging through mucky areas and swatting away bugs.

“One time, I was complaining and was ready to cry,” she says. Her teammate said to her, “Turn it off and do it. It doesn’t help to complain about it.” She learned that sometimes you just have to slog through the rough parts.

How you respond to failure is important, Hogshead-Makar says. Once, when she finished in second place, she blamed her coach for making her train too hard, leading to an injury. She wanted the results to display “an asterisk to explain why I was supposed to win,” she says. But after that, “I took responsibility for my own swimming career—I knew when to push it and when not to.” She learned she was responsible for overuse injuries and for her own health, she says.

Hogshead-Makar’s time at the Olympics taught her to notice and savor the memorable moments. One of her coaches walked onto the pool deck every morning, yelling, “These are the high times—look around you!” and “This is it, people!”

Her experience taught her how to “be coachable toward getting what you want.” After a coach put her in what she saw as an unfair matchup against a teammate, he called her out for not giving it her all. He told her, “You’ve got to bring your A game all the time, even when you’re tired, and even when your competitors aren’t,” she remembers. “Because I had high goals, I wasn’t offended by the way he said it. I could hear the coaching.”

As an executive, Hogshead-Makar has insight on how to get the best out of her employees, much like a coach. When you hire talented people, she says, you can “get out of them things they don’t think they can do.”

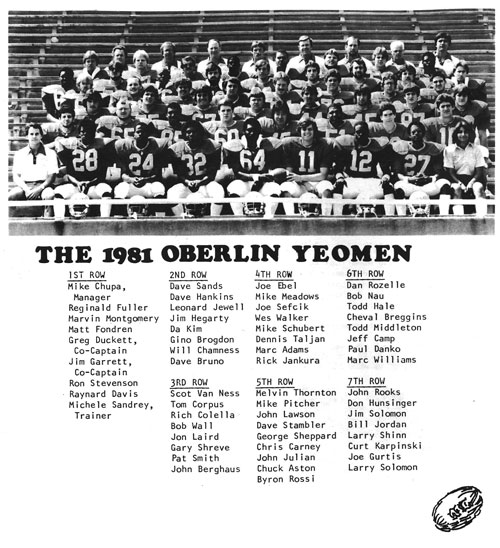

Cheval Breggins was a three-sport athlete at Oberlin before he began his career as an executive at two state psychological associations.Focus on the process, not on winning: I had coaches who never focused on winning. They told us to focus on the mental, physical, and emotional preparation—and then the W’s will come.

The Versatile Talent

Cheval Breggins played on the varsity football, basketball, and track teams at Oberlin College. He’s also a black belt in judo. And he knows a thing or two about the value of versatility.

“As an athlete, you’re always looking for a new technique that might give you an edge,” says Breggins, a former executive director of the Florida Psychological Association and the Michigan Psychological Association who is currently a counselor and advisor at Florida A&M University.

He would watch his opponents closely, hoping to “add a new move to my toolbox,” he says. In track and football, this meant “how to knock off a tenth of a second or catch a pass a little easier.” In the association world, it meant finding ways to step up his leadership game. Being open to new techniques is an important part of professional development, he says.

This drive for continued improvement has framed Breggins’ outlook. When he was in his 20s, he worked for a CEO whose motto was “If it ain’t broke, we fix it anyway.”

“I could relate to that, and most of my colleagues couldn’t,” he says.

Another important element of professional development is “being an objective evaluator of your own performance,” he adds. And sometimes, this evaluation shouldn’t mean measuring yourself against others: In a track event, “I might hit a personal record and still come in dead last.”

As an athlete, Breggins learned the importance of thorough preparation. “I want game day to be easier than what I’ve already put myself through.” Then, “when the competition is bent over, sucking wind, I’m looking at them like, ‘Why are you tired?’”

And that carries over into the executive space—such as anticipating questions and preparing for naysayers before meetings, he says. “Lack of preparation puts you behind before the game even starts.”

Breggins recalls one unexpected event that taught him something about teamwork and trust. Typically, he ran the 100-, 200-, and 400-meter races. On this day, he and his fellow 400-meter runners were asked to run a 4-by-800-meter relay—twice the distance they were comfortable with. The relay’s anchor told the others that as long they got the baton to him within 100 meters of the leading team, he would cross the finish line first.

Breggins still remembers the moment: Each runner did his part to make that happen, and the anchor delivered on his promise.

Sheri Jacobs, FASAE, CAE, didn’t start running marathons until age 29, a reinvention she leaned on when launching her own company in the midst of the recession. (Handout photo)You’re capable of more than you think: I hated running. In soccer, I played goalie, because they didn’t have to run.

The Anti-Runner Turned Marathoner

Sheri Jacobs, FASAE, CAE, recently ran her 30th half marathon, and she has run 14 full marathons. But when she was growing up, she hated running. How did she go from zero to 26.2 miles?

She started running at 29, won a few local races, picked up more speed, and ran the Boston Marathon twice. The fact that she transformed herself from an “anti-runner” to an accomplished marathoner showed her that she could set huge goals and accomplish them.

The “confidence that you can achieve things that seem very big” is important in running a company, says Jacobs, founder and CEO of Avenue M Group, a marketing agency that works with associations. You need confidence to deal with the uncertainty that comes along with running an organization, she says.

Running has also helped her strategize. Succeeding as a long- distance runner requires setting a big goal and smaller goals along the way. As a competitive runner and as an executive, “you have to plan, but you also have to make course corrections when things don’t go as planned,” she says. When things go wrong, “it can paralyze people, but you have to be able to make adjustments.”

Running has given Jacobs perspective on competition. “There will always be somebody who’s faster than you,” she says. “Running is not about competing against other people—it’s about doing your own best.” She started Avenue M Group during the recession, and she wondered where her company would fit in among competitors. “We thought, where’s our space?” and looked for the niche where they could be the best, she says.

Marathon running, even in the best circumstances, entails dealing with adversity. In one Chicago Marathon, the temperature climbed to 103 degrees. Everyone, including Jacobs, was struggling.

“There were so many moments when I wanted to stop and walk and give up,” she says. But she pressed on. When she was two-tenths of a mile from the finish line, the race was cancelled, which meant she could not officially finish, even though she had covered the distance.

“This taught me that they can throw anything at you, and you can get through it,” she says.

In the 2000 Summer Olympics, Derek Bouchard-Hall learned about the pressure of having just one chance to perform at his best.Failure makes you stronger: Being in an environment with lots of setbacks is valuable for developing things like resilience, confidence, and optimism.

The Elite Cyclist

Before Derek Bouchard-Hall became president and CEO of USA Cycling, he was a professional cyclist, national champion, and 2000 Olympian. Cycling has shaped his perspective on leadership and teamwork.

“Sport is a crucible of human endeavor,” Bouchard-Hall says, and “coaches are revered leaders.” Cycling exposed him to a range of leadership styles, including good and bad coaching—and he learned from all of it. In his career, he has tried to mimic the great coaches he’s had, while “adapting it to me personally.”

Bouchard-Hall learned the hard way that what works for one leader isn’t necessarily right for another. He recalls a moment of leadership failure that taught him the importance of “leading in a way consistent with your natural ability.”

He was designated the leader of a team and had to develop strategy. One team member was being obstinate, and Bouchard-Hall decided to take a strong stance and push back in a public way, even though that type of bravado didn’t come naturally to him. It didn’t go well—the other person didn’t back down. He saw that “diplomacy and reason are better sometimes.”

Cycling has also honed his ability to assess a situation. The sport is strategic, he says, and it “enabled me to get good at making a plan in the face of ambiguity.” Also, he adds, “that’s the way organizations work—there is never razor-sharp clarity,” but you have to decide how to proceed anyway.

Competing at the Olympics was “wonderful but super-stressful,” Bouchard-Hall says. “It’s a difficult environment to do your best in,” because of the distractions and the pressure of having one chance to perform well. “It’s difficult to deal with that and focus on what’s at hand,” he says.

He adopted a guiding philosophy: “You can only control what you can control. You have to focus on what you can do and let the chips fall where they may.”

“Sport is hard,” Bouchard-Hall says. You face failure all the time, and it “forces you to develop strength of character.” His cycling experience has helped him deal with setbacks and bounce back from disappointment, on the bike and off.

Nancy Hogshead-Makar and a fellow athlete celebrate her gold-medal win at the 1984 Olympics. (provided photo)

Comments